Tempo, or: What The Guides Don't Tell You

“Activité, activité, vitesse!”

Behavioural science projects thrive on speed. This is a strength. Unlike other change projects, which might require an IT overhaul or org chart restructure, nudges can be designed and delivered quickly. The resulting reputation for getting things done is invaluable for anyone championing behavioural science within an organisation.

But speed has to be fought for. Every step of the way there will be hurdles that try to slow you down. The default outcome, unless rigorously opposed, is that behavioural projects will lose momentum. Projects that lose momentum tend not to recover it. The default outcome is therefore failure! The stakes are high.

Imagination vs. harsh reality

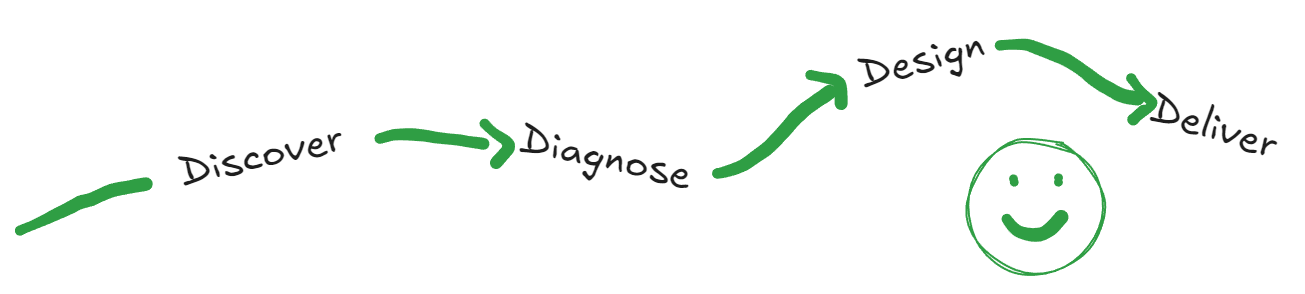

Many of the 'how to run a behavioural science project' guides

(BETA's 4D framework, or

BIT's TESTS,

for example)

describe a very orderly

and sensible-looking approach. Perhaps you have a six-month deadline to complete your project. Working from the framework,

you duly schedule in month 1 for establishing the scope, month 2 for identifying outcomes and mapping behaviours,

month 3 for researching the context, month 4 for designing interventions, month 5 for implementing them,

and finally month 6 for assessing their effects and reporting back. This is what we might imagine it looks like:

A plan like this is a GUARANTEE OF FAILURE.

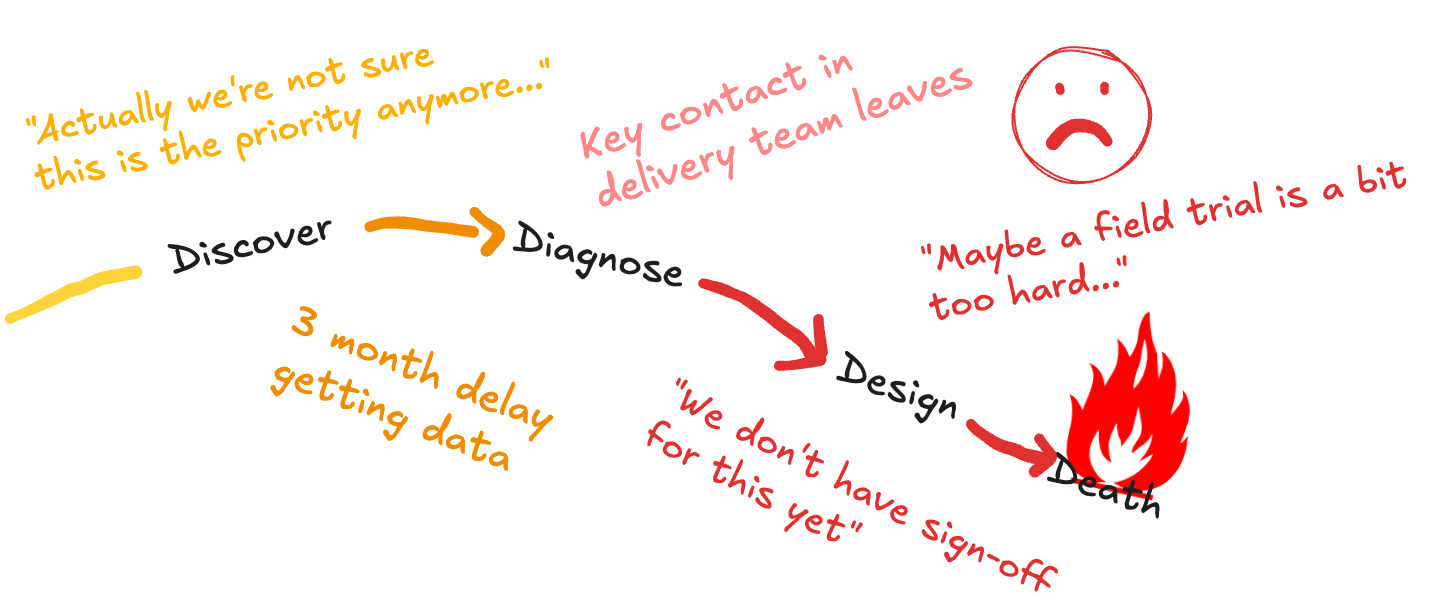

Here are some of the things that will happen if you try to follow it:

- There are personnel changes in the team you're working with. Half of the people you spent month 1 getting buy-in with are reassigned to different projects.

- When you request the data you need to do your analysis in month 3, you discover that there is a six-week delay.

- After you've done your research, you realize that the 'problem' you are looking at isn't the real issue at all.

- Leadership priorities shift at short notice, meetings get pushed, funding gets reassigned.

Now your project looks like this:

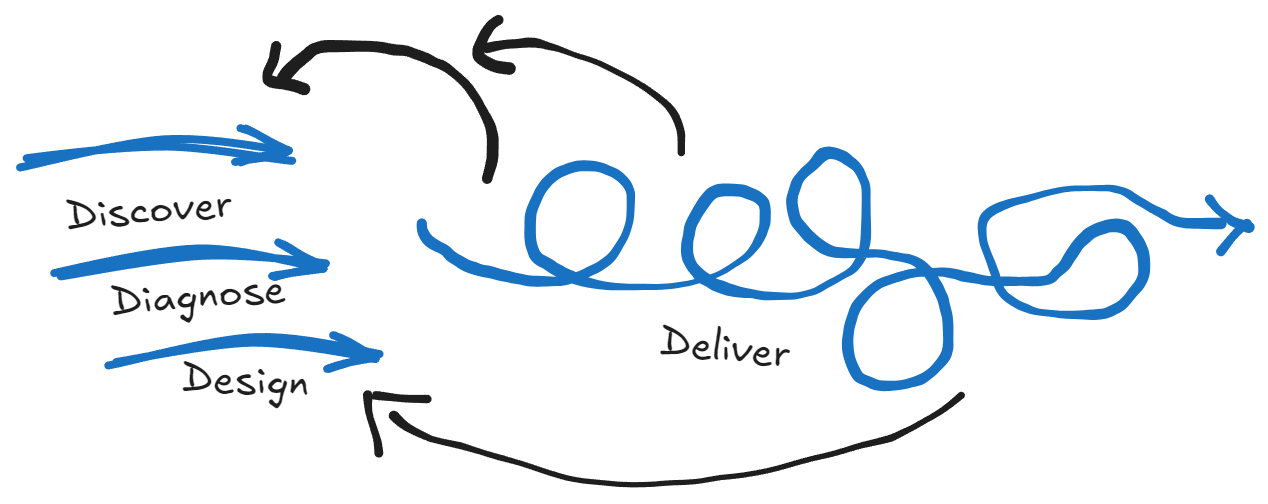

The best protection is to move fast. Rather than sensibly spacing out all the stages of the project over months, you are much better off trying to get a quick and rough version done quickly. If you can work out in week 1, or better still day 1, that the project is targeting the wrong thing, you've got time to pivot. If you can find some useful insights immediately by going out and speaking to people and sending a quick memo back to the project sponsor, they can be reassured you know what you're doing, and are more likely to back you later. If you can get a gut feel for what the solutions might be very quickly, then you can start working on how they can actually be implemented. Then, when things inevitably do go wrong, you will have the time, budget, and goodwill to recover.

How to go fast?

How can you achieve this sort of speed? The good news is that the quick version of many project activities will give you most of what you need:

- Reach out to a handful of experts already working in the space. An hour questioning an expert can be worth a week trying to sift through an unfamiliar literature on your own.

- Don't spend weeks perfecting your fieldwork plan. Get in the car or on the train today and go see for yourself. Seek forgiveness rather than permission.

- Write memos. Put pen to paper on what you're seeing and hearing. Share these widely.

- Take an early guess at what a solution might be - it's fine to change it later. Use your mental library of frameworks to generate good ideas quickly.

- Work in parallel. You can be out doing fieldwork while you are waiting to get access to data. You can be brainstorming solution ideas at the same time as you run a user survey. Write up and share your site observation notes on the train home.

If you manage some of the above, you are giving your project at least a chance of success. Which is more than most have!

With a lot of hustle and healthy paranoia, now your project might look like this:

The hidden benefit of tempo

And it's here we should mention the final enormous benefit of tempo. Here is a rough hierarchy of behavioural science project outcomes, from worst to best

- ★☆☆☆☆ Failure: The trial backfired, or the project fell apart in a way that caused damage to the reputation of behavioural science in your organisation.

- ★★☆☆☆ Mediocre: Your immediate stakeholders might be happy, but not much changed as a result of the project. Once you net out the costs and time spent, no real impact.

- ★★★☆☆ Good: A trial which results in a small operational improvement; a report which contributed in some ways to policy decisions; some internal capability created, some trust and goodwill created.

- ★★★★☆ A great project: Real impact on big problems; a working intervention that gets implemented and stays implemented.

- ★★★★★ A superstar 'unicorn': A successful intervention that gets scaled up, or generates new ideas and evidence that are learned from and adapted around the world.

There are superlinear returns from moving up the scale. The impact of a 4-star project is something like 10x the impact of a 3-star project. The impact of a 5-star project is 10x again the impact of a 4-star project. Like venture capital funds' returns, approximately all of behavioural science's total practical impact on the world comes from a relatively small number of 4- and 5-star projects. One such is the UK's switching the default on pensions to automatic enrolment: it significantly increased the proportion of workers of all ages saving into a workplace pension (from 20 percent to a whopping 88 percent for 22- to 25-year-olds). There is an argument to be made that this one nudge has had as much impact as all the others put together.

This is not to put down projects with more modest outcomes: they are essential for building the momentum and goodwill that makes it possible to launch superstar projects in the future. But when applied behavioural scientists look back on their careers, it tends to be one, two, maybe three projects out of dozens that really made a difference.

So for any given project, you want to give yourself a swing at a real home run. If you do things the 'normal' way, and get bogged down, when you spot an opportunity to make your intervention much more ambitious ("what if instead of sending a letter explaining how to fill in this form, we used the data we already hold to design out the need for the form altogether?"), you won't be able to take it. Or maybe you have to scrap the randomised controlled trial for lack of time, or money, or because your senior backer has moved on. Now, without proof that it works, the chances that your intervention gets scaled up within your organisation, or copied elsewhere, go down a lot. To give yourself these opportunities, you've got to go fast.