How to Generate Value Quickly with Communications Nudges

Organizations send out a lot of communications to their customers, users, and employees. These include letters, emails, website landing pages, software user interfaces, and text messages.

Often, these communications are not very good. Certainly they have not been optimized with behaviour in mind. For example, it's common to see letters whose entire purpose is for the recipient to take some action - to sign up for a service, to send an electricity meter reading, to provide the police with a witness statement after a traffic collision - but where the 'what', 'why', and 'how' are buried in paragraphs of jargon.

An hour spent rewriting a bad communication can double the rate of people completing the target behaviour, forever, for free. Even when the starting point is pretty good, there are usually multiple percentage points of improvement to be had. Many messages get sent day in, day out, in their hundreds, for years: so this is an enormous ROI from a small one-time effort.

But over a decade helping companies and governments with behaviour, I've noticed that these relatively free lunches are rarely pursued as vigorously as they could be. If you're starting to think about how to apply behavioural science in your organisation, this represents a big opportunity!

If you want to learn more about systematically applying behavioural science to your work, sign up for updates below:

A simple procedure for improvement

So how do we seize this opportunity? In our experience a good re-draft can be done in about an hour. Here's the procedure:

- Get in a room with a handful of people, including the organisational 'owner' of the letter who knows all about who it's sent to, when, how, and why. It also helps to have someone on hand who has never seen it before and knows as little as possible about it (this can be you!).

- Put the original communication up on a large screen or projector. Don't edit it directly. Instead start a blank document and put it side-by-side with the original. You may end up reusing some content from the original, but nothing gets included by default. Every word has to earn its place.

- Now write the shortest, most direct version of the letter you can. A great trick is to ask the owner questions like: "What is this letter basically saying?" or "If someone came to you confused about this letter, what would you tell them?". Nine times out of ten, they'll' be able to reel off a very clear, plain-spoken explanation - even if the original letter itself is not clear at all! Write down what they say, word-for-word, and you'll have an excellent first draft to work with.

- Focus on the target behaviour, with clear calls to action and simple descriptions the steps involved. Your bread and butter here is a call to action: in a single phrase, what do recipients need to do? This should be at the top, in large font, in bold.

- Add selected persuasive ‘nudge’ messages to encourage the target behaviour. 2-4 is usually the right number. If you brainstorm for a bit (and click through some frameworks) you will usually find you have way more possible messages than you can fit. Interviews and focus group transcripts with the target audience are of course a goldmine. Once you've got your candidates (maybe 20-30 of them), list them out on a whiteboard and number them off. Then mix, match, and experiment until you find the combination which hits the hardest.

Case Study

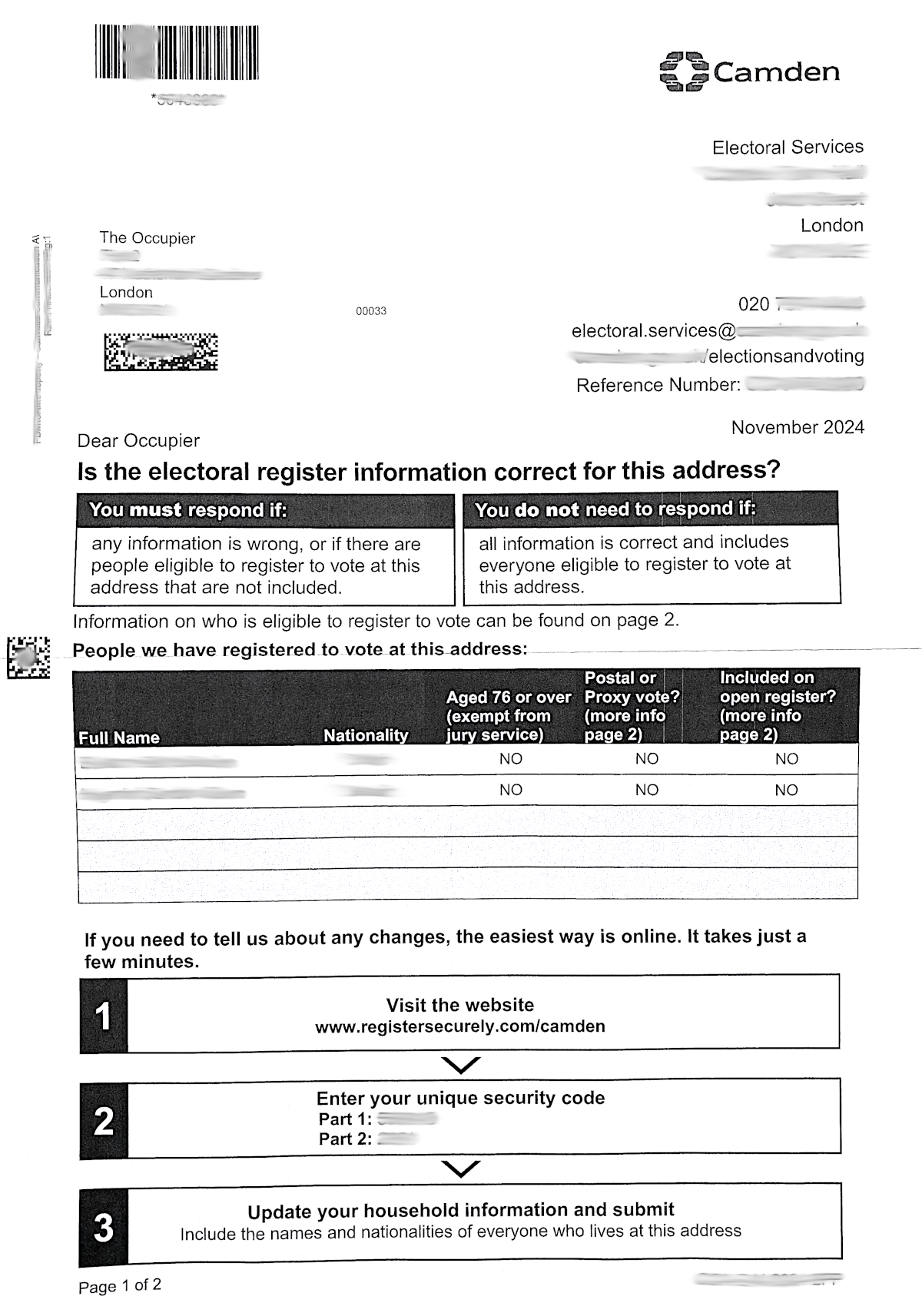

Let's look at how this works in practice. Below is a real letter I received just this week, and the behaviour it wants of me is pretty simple: first, check if my details on the electoral register are correct; then if they're not, to visit a website and update them. It's not terrible — I've seen much, much worse — but there's room for improvement.

What to make of this letter? Even before we start reading the test, the overall impression is busy. The margins are narrow and it's covered in different types of 'stuff': we've got text and tables and boxes and more boxes.

It's also long. Not as long as some, and to its credit it puts the important information on the first page. But the total word count is 800 and its Flesch-Kincaid Reading Grade is 12, which equates to a college-level reading difficulty. (If we're more generous and exclude the extra information on page 2, this falls 300 words at an 8.5 grade level.)

At this point it's a good idea to try the 5 second test. To perform this test, you need to find someone who hasn't seen the letter before, have them flip it over, count to 5 (about the envelope-to-bin life expectancy for many letters), and then take it away again. If they can tell you the gist of what the letter is and what action they need to take, then it passes. If not, there's work to do.

Our first step is just to simplify and cut. We'll get rid of the extra formatting elements. These feel good when you're adding them, making the result look more 'design-y'. But 'design-y' isn't the same as 'very easy to understand and act on', and it's the latter we're optimising for. (Note: At this stage it's better to cut too much than too little. We can always add things back later.)

Here's a revised version that took about 5 minutes to do:

| People registered to vote at this address | Nationality | Are they aged 76 or over? | Do they need a postal or proxy vote? | Are they included on open register? |

| Joe Bloggs | British | No | No | No |

| Jane Doe | British | No | No | No |

- Visit the website: www.registersecurely.com

- Enter your unique security code: Part 1: 12345 Part 2: 6789

- Update your household information and submit. Include the names and nationalities of everyone who lives at this address.

We're down to about 125 words now - less than half the original. Often at this point you're already close to a finished product: every additional word has to earn its keep. Note that it now all fits on one page, including the sign-off. If our lawyers force us to keep some of the content on the back page (ideally after its own trim and simplification) we now at least have a clear hierarchy: page one is the core message, page two (after the sign-off) is the optional extra info. This helps us preserve the at-a-glance reaction we want from our recipients, namely "This looks simple and easy".

Now we can brainstorm additional messages. For a letter like this, not too many are needed because the behaviour is quick, simple, and uncontroversial. Here are some options:

- Why it's important to keep this information up to date;

- How the information gets used behind the scenes;

- A reciprocity angle: "Do this for us so we can do something for you";

- A social norm, along the lines of "The vast majority of people keep their information up to date, don't be one of the few who doesn't";

- Something about the consequences of getting it wrong;

- Personalisation

For me a crisp sentence on why it's important — and not just pointless busywork — feels most compelling. A rough version might be: "Being on the electoral register is important: it lets you vote and access credit checks, and it helps us keep elections fair and transparent". Let's also add a named sender for a minimal personal touch:

| People registered to vote at this address | Nationality | Are they aged 76 or over? | Do they need a postal or proxy vote? | Are they included on open register? |

| Joe Bloggs | British | No | No | No |

| Jane Doe | British | No | No | No |

- Visit the website: www.registersecurely.com

- Enter your unique security code: Part 1: 12345 Part 2: 6789

- Update your household information and submit. Include the names and nationalities of everyone who lives at this address.

This simple procedure is very likely to result in a letter that will perform multiple-percentage-points better than the original.

How to pick your targets

The best communications to work on have the following properties:

- Intended to prompt action rather than just for information;

- The action they're prompting is important;

- High volume;

- Likely to persist: e.g. do you expect still to be regularly sending out a very of it a year from now?

- Headroom to improve: the worse the current version, the better;

- Ability to actually make changes;

- Data on what happens next: can you tell which recipients do the behaviour and which don't?

If you've got lots of potential options — many organisations will have hundreds, all of which could use improvement — try printing them out and arranging them on a large table. Sort them into priority order using the criteria above, perhaps as a physical 2x2 matrix with importance/volume on one axis and feasibility of improvement on the other.

Compounding returns

If you can pick a handful of communications and then run the procedure above on each of them, you'll soon have a great portfolio of examples showing quick, practical improvements.

This creates options. Communications are excellent candidates for simple randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (further blog to follow on how to do your first simple RCT). These can quantify the effect of your changes on behaviour (and demonstrate the money saved and return on investment). If you've got multiple good options for the nudge message, an RCT can adjudicate between them.

They also generate organisational momentum and understanding for behavioural science. When we were in the Nudge Unit in the 2010s trying to persuade the UK government of this approach, these night-and-day improvements — especially when backed by RCT results — were our entrée into departments who would not otherwise have given us the time of day. If you want to pursue more ambitious applications of behavioural science within your organisation "This sounds fancy but it's really just systematised common sense, and here are the practical wins we've achieved already" is a great pitch to be able to make.

A final note. There is a snobbish strand of behavioural science commentary that dismisses communications nudges as somehow trivial. Don't listen! Anyone who has designed and deployed an intervention that actually changes behaviour deserves respect and encouragement: changing behaviour is hard! Many of the people who write off 'simple nudges' have zero examples of successful behaviour change of their own to point to - simple or otherwise. So remember: if you're actually shipping interventions and they're working, then you're lapping most of the field already.

A question for you

If you're working on a communication nudge, we would love to hear from you. What's been the single biggest challenge you've faced? What's gone better than expected? What would you like to know more about? Drop us a line at info@nudgepartners.com.

Or if you've got a 'room for improvement' communication in mind and you would like to test out the approach by working through a real example on a call together, request a free consultation below:

Request a ConsultationSome useful links

- Hemingway App: very useful tool for simplification, giving you immediate feedback on which sentences are likely to be hard to read. Not all of its advice needs to be taken literally

- How to use Microsoft Word's inbuilt readability tools (including Flesch-Kincaid scores)

- How to interpret the resulting Flesch-Kincaid scores. There are other readability metrics but they tend to be very correlated with each other, so F-K is generally fine as a rough indicator

- Behavioural Science Aotearoa's guide to simplifying a message