Developing Your Behavioural Problem Antenna

A lot of your impact as a behavioural science champion will be determined not by how hard you work, but by what you choose to work on. While some problems can be solved with pretty simple behavioural interventions, others will resist months or years of painstaking effort.

So how do you work out which is which?

First, there is a trap to avoid. One might reasonably claim that "we should use behavioural science when there is a behaviour we want to change". One might also suggest that "(almost) every problem is behavioural problem". After all, behaviour is just people doing things, and people are everywhere!

But combining these claims gets us into trouble. Our answer to which problems we should use behavioural science to fix is now 'all of them'. This might make us feel important, but it is useless as a guide to action.

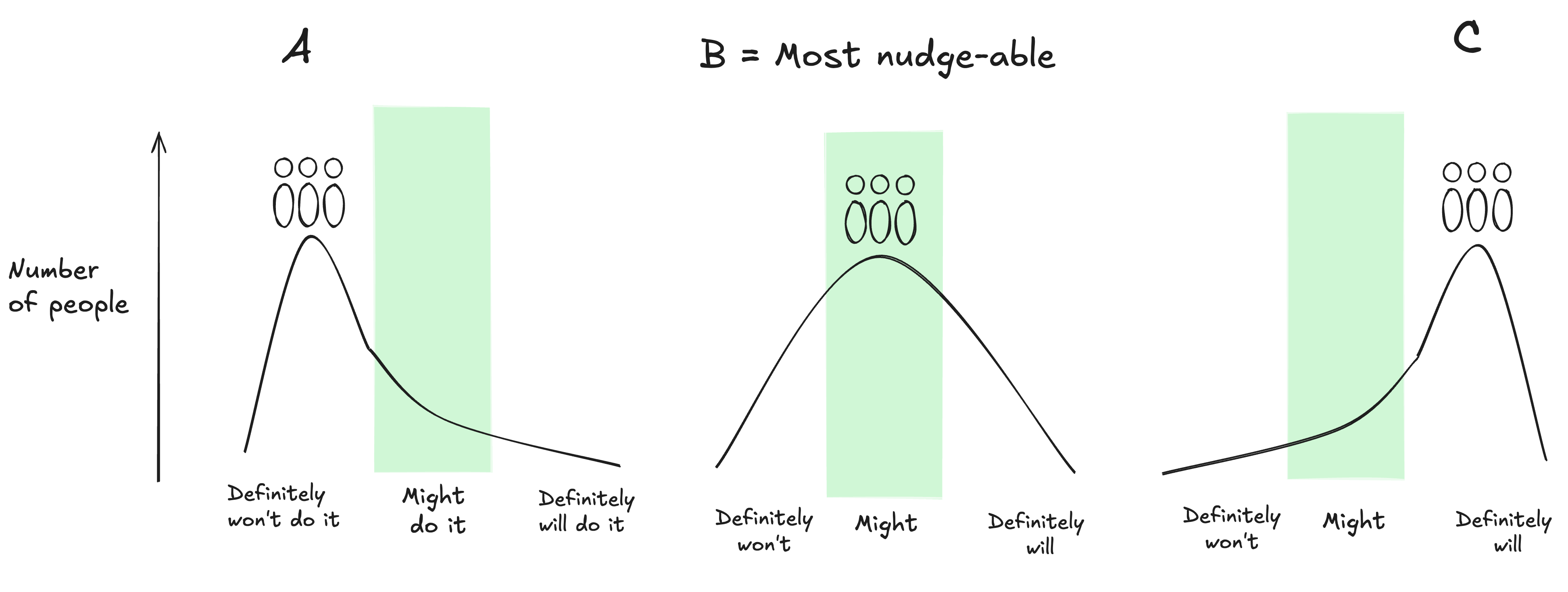

The behavioural sweet spot

To improve on this, we can try to define a 'behavioural sweet spot'. Characteristics of the sweet spot might include:

- Most people's current behaviour is not entrenched one way or another: a nudge might be enough to swing them over (B in the image below). Joining the organ donor register is a much-nudged decision for this reason: for most of the population it's not a question they've given serious thought to, so whether and how that choice is presented to them can be decisive.

- The problem is behavioural rather than structural. If we fixed the behaviour, the problem would go away. I once worked on a project trying to reduce plastic use on a Pacific archipelago where the government had contracted to receive and 'recycle' a monthly shipload of rich countries' plastic waste. While those ships kept coming any behaviour change intervention on the islands was doomed to insignificance.

- We have good opportunities to change the behaviour: you want control over the 'touchpoints' people encounter as they make the decision we want to sway. One of the classic early studies by the Behavioural Insights Team was helping people back into work by redesigning the initial contact with UK Jobcentres, so that initial work-focused conversations happen much sooner. This project was only possible because a jobcentre manager in Loughton controlled the relevant touchpoint - the setup of the jobcentre - and was on board to experiment with changes.

- A project looking at the behaviour would be set up for success, with senior support, good data, the ability to make changes, and the ability to track results. Ideally, you want to be part of the solution to a problem that is already keeping executives up at night.

These sorts of tests are a very helpful start. But they gloss over a key intuition about what we are really trying to achieve with behavioural science, one that, as a behavioural champion, you want to cultivate assiduously.

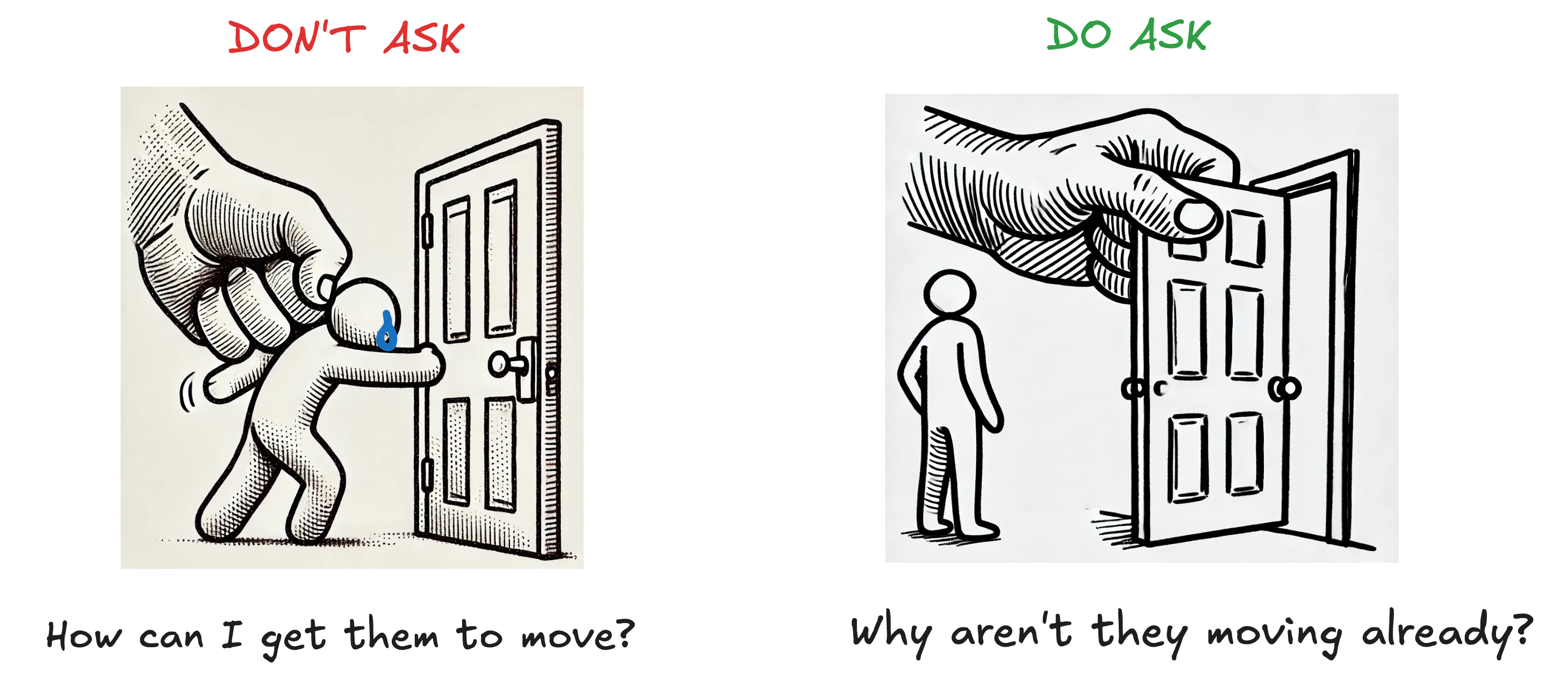

Lewin's powerful question

For this, we need to turn to Kurt Lewin, the founding father of modern social psychology. His great insight, what Daniel Kahneman referred to as Lewin's question, is that changing behaviour is a matter of asking not "How can I get them to move?" but instead "Why aren't they moving already?".

Imagine we're a company running a special discount scheme for loyal customers, or a government offering a subsidy that reimburses small businesses a portion of their R&D costs. It's essentially free money, and our end user research suggests that there's a lot of interest and demand. But people aren't signing up for it. What should we do? Following Lewin's advice, we investigate why people aren't moving already; what's stopping them?

It turns out that the online form is incredibly complicated, with dozens of questions, and the webpage times out if you're not quick enough answering them. People are getting to the form but then giving up in frustration soon afterwards. In this situation, it would be folly to try to push harder by increasing the size of the discount or subsidy, or by running a big advertising campaign. All this will do is send more people to the form, only to have them bounce off again. We would be pushing on a bolted door. Instead, we need to unbolt the door: make the form much simpler, use the data we already hold to autocomplete it, or get rid of it altogether.

Hunting for good behavioural problems is an exercise of looking around the organisation for these bolted doors. Other ways of asking this are:

"What doesn't make sense here?"

or

"Where are people acting against their own long-term best interests?"

If we are offering people free money and they aren't taking it, we need to notice that something strange is going on. It should set our behavioural antenna buzzing. These are people and situations which do not need to be pushed on any harder. If we can snip the restraints that are holding people back, then the positive forces already at play - monetary incentives, the social pressure to get a job, wanting to be healthy, the desire to be a good parent, or a good student - will do the rest.

Suggested Reading

- Chapter 2 of The Person and the Situation by Lee Ross and Richard E. Nisbett, on Channel Factors

- Sections 5 to 9 of BETA's Guide to developing behavioural interventions for randomised controlled trials

- You and Your Research by Richard Hamming